The ‘Cog in the Wheel’ and the Perils of having your ‘Prime Rib’ Everyday

Dr. Joel J. Napeñas

8 minute read

While I was a dental student more than 20 years ago, I was introduced by my classmate to the book “Rich Dad, Poor Dad”. He told me that it is a different way of thinking. So I read it, and while the concepts were intriguing, I concluded at the time that it didn’t apply to me. The book told us to accumulate assets, (e.g.: real estate) that were going to generate income for you, but didn’t really tell you how. I rejected the concept, or at least felt that it was so far-fetched for me. My limiting beliefs at the time were that only people with a lot of money could buy real estate, and that investing, business ownership and real estate were risky. And besides, if I was going to pursue the career that I really wanted, it wouldn’t matter because I was going to do something that I love and be paid well doing so.

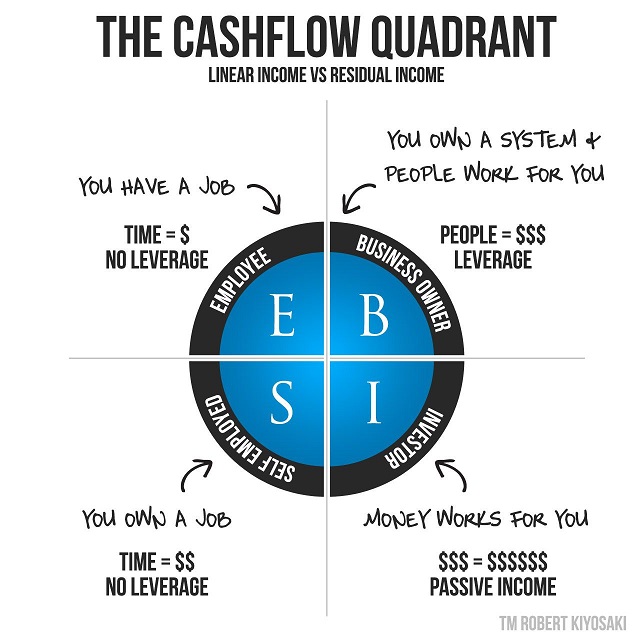

While “Rich Dad, Poor Dad” sat on my bookshelf all those years, I went down the path of “Poor Dad” and opted for and sought jobs that had the steady stable income. So, by definition of the book’s cash flow quadrant, I became a career ‘E’ (employee), someone who ‘had a job’ albeit well paid ones. Most of my colleagues are small business owners, in the ‘S’ (self-employed) quadrant in which you ‘own a job.’

The traditional advice we were given by our parents and role models were as follows: go to school, get good grades, get into a good university, do well in school so you can get into the program that will get you a good job and make you a good living (i.e.: dentistry), graduate, start working, earn enough to support yourself and your family, work for 30-35 years, hopefully retire to a life of the beach and playing golf, and hope that you are healthy enough to enjoy it when the time comes.

We want the prestige of attaining a respective profession that would make us a good living, and hopefully it is something that we are interested in and passionate about. For me it was medicine and having the prestige of being called ‘doctor,’ solving problems, helping patients feel better and get healthy, while earning a good living doing so. I didn’t get into medical school but I did get into dental school, which I thought was the next best thing. I was told that dentists make more money and had more autonomy in their practice. But throughout dental school, in those days of waxing teeth, pouring stone models, carrying around my tackle box of instruments and begging patients to come in because showing up was the difference between me finishing dental school in four years versus five, I had this sinking feeling that dentistry wasn’t for me. But since I was there in a program that was so hard to get into and heavily invested in it from a time and monetary standpoint, I thought that I would learn it and perhaps maybe learn to eventually like it, and once I earned the ‘big bucks’ that it wouldn’t matter.

Fortunately, I accidentally stumbled upon a specialty, Oral Medicine, that was more aligned with my passion of medicine, and have built a successful career out of it. But it was done at a heavy price for me. First, having a career in my specialty is not as financially rewarding as being a general dentist, and other dental specialties. But the biggest price was having to move away from my family, friends and loved ones back home in Canada in order to pursue the limited desirable opportunities in the specialty and to earn a decent living that is comparable to that of my colleagues. Not a single day goes by where I don’t miss my family and friends back home. Sure we can see them a few times a year, but it just isn’t the same (and the pandemic has prevented us from seeing them for an extended period of time).

It’s been 20 years since I graduated from dental school. What have I learned since?

While we spend all of our schooling days working hard to get into the profession, and our early years establishing ourselves, midway through one’s career, what do we focus on? Getting out of the profession…or at least having the flexibility to do so. Don’t get me wrong… I love what I do. I love treating patients, I love connecting with them, I love the people I work with, I love solving complex problems that haven’t been solved after seeing many other physicians and dentists, and I love mentoring and training young docs to do the same. I still thoroughly enjoy what I do, and am privileged to happen to do something that I love.

But here is the rub. Let’s say that your favorite food in the whole world is prime rib. Now what if someone told you that, in order for you to survive, you have to eat prime rib at the same restaurant three meals a day, every day, for the next 30-35 years? That can get pretty old.

We work so hard to get the privilege to eat our ‘prime rib.’ But after many years of eating it every single day, you want to have the flexibility to indulge in other things, like ‘salmon,’ ‘sea bass,’ ‘sushi,’ or even an occasional ‘Big Mac.’

Those of us in higher paying professions are no different than other ‘nine to fivers,’ only that we get paid more by the hour (and for many of us, we have to work way more than nine to five in our job). We are all the same… We are all ‘cogs in the wheel,’ in an assembly line factory that produces ‘widgets.’ We get paid by the number of patients we see, crowns that we cement, hygiene checks that we do, teeth we extract, stainless steel crowns we place, braces that we put in kids, or surgeries in the hospital that we perform. And it doesn’t matter whether you are a small practice owner or a W2 employee. In that sense, we are no different than the line worker at the factory, or barista at Starbucks. Our inputs (i.e.: our work, our time, our production) directly correlate with our outputs (i.e.: $$). In other words, if you don’t work, you don’t get paid.

But since we get the false sense of security and feel the prestige of being a higher paid professional, we do the things that people with a little more money do. Buy the nicer house, take the fancier vacations, get the nice car, and put our kids in the best private schools. We believe that we worked hard to get to where we are at, that we deserve it, and so we consume more. The more we consume, the more ‘widgets’ that we need to personally produce. The more we need to produce, the more time it takes away from doing other things. The more we need to be that ‘cog in the wheel.’

We have been trained to get the good career in which you work hard so you can make a good living and have a good life. But is a good life simply all about taking on student debt so you can get the ‘good job’ that occupies most of your waking hours for the next 30-35 years so that you are paid well enough in order to pay off your student loans over the next 10 years (if lucky), get that nice car that you will pay for the next 5 years, get that house that you will pay for the next 30 years, and maybe have a week or three (if you’re extremely fortunate) to take vacations with your loved ones?

Yes, you can take more continuing education courses to learn the next big technique that will earn you more income, or drive greater efficiencies and production for you and your staff. But you’re still a cog and you have to produce ‘widgets,’ and you’re still forced to eat that ‘prime rib’ every single day, and not by choice.

There is nothing wrong with being a cog and it is a privilege that we get to eat our ‘prime rib’ every day. But we need to think beyond what we were traditionally taught that leads us to a life destined to alternate between producing and consuming for the next 30-35 years.

It is fairly recently that I dusted “Rich Dad, Poor Dad” off the shelf. This time, it resonated with me after almost 20 years of being that cog, and being that ‘E.’ I realized that there is a better way. We need to learn to become the owner of a ‘factory’ that employs the cogs and makes the widgets, and have the option to take yourself out of the machine, operate it, or better yet, supervise it passively. That’s either by creating something, or investing in or owning assets that don’t directly rely on your inputs to generate outputs. It is by being either a business owner (a ‘B’) or an investor (an ‘I’.)

The greatest benefit of having that flexibility and variety? At least for me, these days I enjoy and appreciate that ‘prime rib’ even more because I know that I will be doing it by choice and not entirely by necessity. Every day is not ‘just another day’ in the office or practice. And when you appreciate, are more engaged, and enjoy it even more, you are better at it and more effective serving others in your vocation.

You can have that ‘prime rib,’ how much you want and when you want, yet have the freedom and flexibility to have that ‘sushi,’ ‘chicken’ and even that ‘Big Mac’ too.

Dr. Napeñas, a practicing academic dental specialist in Oral Medicine, is founder and managing partner of 5DH Partners, a real estate investing firm that helps dentists and other professionals build wealth and generate passive income through investing in multifamily properties.

Want to learn more about investing in real estate without being a landlord?

Subscribe to our email newsletter here.

Set up a time to talk with us personally here.

Download a copy of our free e-book here to learn how dentists and other professionals can replace their income by passively investing in real estate.

Visit our Facebook and LinkedIn page, or join our newsletter mailing list for articles, updates and opportunities.